Did you know that Elon Musk has a brother who sits on Tesla’s Board of Directors? That’s right, Kimbal Musk is an entrepreneur in his own right, and Tesla isn’t alone. 30% of the S&P 500 are actually family businesses. From Walmart’s Walton to Germany’s BMW, these firms balance family ties with professional success. This guide explores how these organizations blend heritage with performance to build lasting advantages.

What is a Family Business?

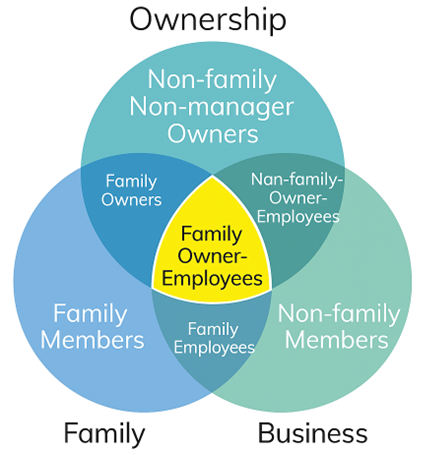

A family business, sometimes called a family firm, is an enterprise where ownership, management, and governance overlap among family members. These roles are often illustrated through the three-circles model, which shows how individuals can simultaneously inhabit “Family,” “Ownership,” and “Management” positions, each with different motivations ranging from emotional legacy preservation to financial returns and strategic control.

What defines a family business? The key characteristics include:

- Family ownership: Family members’ substantial equity stakes

- Family management: Family members’ active involvement in daily operations

- Family governance: Influence on business direction and strategic choices

- Intergenerational vision: Plans for transferring leadership across generations

Types of Family Businesses

There are several types of businesses, each involving different levels of family participation These include:

Founder-Led Enterprises

Businesses with just one generation in which the founder keeps all authority but starts to include family members in important positions and decision-making. With this arrangement, the founders can progressively transfer duties while maintaining final control over the company’s vision and strategic direction. This model is demonstrated by private corporations such as Cargill and Mars, where family supports the founder’s leadership vision while contributing specialized expertise.

Sibling Partnerships

Second-generation businesses run by multiple family participants, frequently siblings, who divide up the leadership duties. When the founding generation transfers authority to their offspring, a collaborative leadership model is established in which siblings work together to manage various business operations. Sibling partnerships can benefit from complementary skills, but in order to manage possible conflicts and preserve both family harmony and business effectiveness, clear decision-making procedures and clearly defined roles are necessary.

Family-Owned Private Companies

Are large private companies with no public shareholders, where families retain total ownership and control. These companies maintain family values and culture while enjoying long-term strategic flexibility and decision-making autonomy. This group is exemplified by Koch Industries and Mars, Inc., which show how these businesses can grow significantly while maintaining operational privacy and total family control.

Multi-Generational Dynasties

Reputable brands that have effectively passed ownership and management down through several generations, frequently over decades or even centuries. In order to preserve family ownership while adjusting to shifting market conditions, these organizations have created complex governance structures, succession planning procedures, and cultural preservation techniques. The Tata Group in India and the Wallenberg in Sweden are two examples of how these businesses can adapt and prosper during generational changes.

Family-Controlled Public Companies

Publicly traded companies where founding families maintain controlling interests through concentrated ownership structures while accessing public capital markets for growth financing. This hybrid model allows families to retain strategic control and lasting vision while benefiting from increased liquidity and capital availability. Walmart and Bosch represent this category, demonstrating how these companies can scale globally while preserving family influence over corporate governance and strategic direction.

The Advantages of Family Businesses

Long-Term Perspective

They frequently embrace longer time horizons, in contrast to publicly traded corporations that prioritize quarterly earnings. Strategic investments in R&D, market expansion, and business succession planning are made possible by this patient capital approach, which removes the need for quick returns.

Research shows impressive performance metrics from PwC’s Global Family Business Survey 2023:

- 43% of these enterprises achieved double-digit expansion

- 71% reported increased revenue in their most recent fiscal year

- Companies with clearly defined family values and purpose were especially likely to achieve strong growth

Emotional and Social Capital

These organizations excel at balancing three types of capital:

- Emotional capital: Maintaining family legacy and unity

- Financial capital: Generating returns and funding expansion

- Social capital: Building reputation and stakeholder relationships

Financial Transparency

Despite perceptions about opacity, family-owned companies often deliver higher-quality financial reporting. Studies indicate they engage less in earnings manipulation and demonstrate greater transparency compared to non-family counterparts. In some regions, employing high-quality auditors particularly Big Four firms has been shown to strengthen trust and reduce agency conflicts in these companies (MDPI). “This reflects reputational concerns that prioritize stakeholder trust over short-term financial engineering. However, ESG disclosure analysis remains challenging even for these transparent companies

Challenges Facing Family Enterprises

Socioemotional Wealth Protection

To preserve socioemotional wealth, family control, reputation, and legacy, these organizations occasionally underinvest. Conservative strategic choices, such as low R&D expenditures, constrained diversification, and opposition to acquisitions or outside funding, may result from this.

Principal-Principal Conflicts

Concentrated family ownership can lead to disputes when family insiders put their own interests ahead of those of minority shareholders. This can result in governance issues that can harm stakeholder trust and business performance. Usually, these disputes start because of:

- Nepotism in hiring and promotion decisions, where relatives are given jobs based more on their connections than their skills

- Family members receiving preferential loans or other financial agreements at below-market rates, which essentially use business resources to fund personal endeavors

- Through related-party deals, self-dealing agreements, or transfer pricing schemes, family ownership enables resources to be “tunneled” away from the company at the expense of minority shareholders.

Succession Planning Difficulties

The transition between generations represents the ultimate test for multi-generation firms, with many failing to survive beyond the second or third generation due to inadequate succession planning. Founders often delay these critical conversations until health crises or market pressures force hasty decisions, leaving potential successors unprepared for leadership responsibilities.

Common succession planning challenges include:

- Delayed leadership development and mentoring processes

- Conflicting family member visions for business direction

- Lack of objective performance evaluation criteria

- Insufficient tax and estate planning coordination

- Communication gaps between generations

- Unclear ownership transfer mechanisms

Family stakeholders also usually hold divergent opinions regarding the degree of business involvement and strategic priorities. These disputes have the potential to cause crippling internal tensions that splinter family ties and business operations, underscoring the necessity of formal succession plans put in place long before leadership changes are required.

What Makes Family Businesses Last: Best Practices for Success

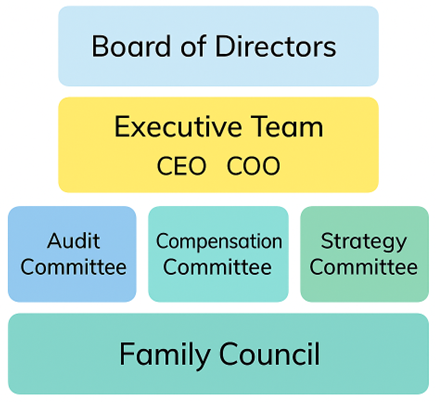

Professional Governance Structures

Implementing formal corporate governance mechanisms significantly enhances performance:

Board Excellence: Companies with diverse boards, including external or non-family directors, are more likely to achieve double-digit expansion. Studies indicate that family-run businesses with independent board composition demonstrate higher environmental disclosure and stronger overall oversight, as outside directors bring fresh perspectives and strategic rigor while reducing insularity.

Advisory Committees: The quality and transparency of decision-making are enhanced by specialized committees for strategic planning, audit, and compensation.

Codes of Conduct: Operational clarity is produced by well-defined policies controlling ethical standards, family member involvement, and dispute resolution.

Digital Transformation

Family firms with strong digital capabilities consistently outperform their peers. Technology improvements support:

- Enhanced internal decision-making processes

- Improved stakeholder communication and trust

- Better transparency in operations and financial reporting

- More efficient succession planning and knowledge transfer

ESG Commitment

Environmental, social, and governance commitments increasingly drive success in these enterprises. Companies with strong ESG practices demonstrate:

- Higher levels of environmental disclosure

- Better oversight and accountability

- Stronger stakeholder relationships

- Enhanced long-term sustainability

Professional Management Integration

Bringing in skilled external managers while maintaining family vision creates powerful synergies. British firms like JCB and Wates demonstrate how blending family ethos with professional management drives enterprise evolution and scale.

Is Starting a Family Business Hard?

These firms present unique challenges beyond typical entrepreneurial hurdles, requiring careful navigation of both business and personal dynamics. These challenges commonly include:

Relationship Management: It takes extraordinary emotional intelligence and communication skills to strike a balance between family ties and business decisions in order to keep personal disputes from compromising professional goals.

Role Clarity: As the company expands, confusion and conflict can be avoided by clearly defining roles and decision-making authority, which also guarantees that each individual is aware of their unique contributions and limitations.

Professional vs. Personal: Relatives can maintain their personal ties while making difficult business decisions by keeping business conversations and family time apart. This promotes healthy relationships and impartial decision-making.

Capital Requirements: Even though privately-held companies might have access to patient capital, it can be difficult to raise enough money for expansion while keeping family ownership, particularly when outside investors demand equity stakes or changes to governance.

However, these challenges are often offset by significant competitive advantages including patient capital access, aligned family values, and built-in trust. Success typically depends on establishing clear governance structures early and maintaining formal family constitutions that separate business decisions from personal relationships.

Global Examples of Successful Family Enterprise Models

The Wallenberg Dynasty (Sweden)

The Wallenberg family offers a compelling example of transparent succession planning and sophisticated governance structures. By using foundations to separate ownership from management while openly communicating roles and governance processes, they have successfully mitigated infighting and established high standards for organizational continuity. Now transitioning into the sixth generation, their governance model demonstrates how well-designed institutional frameworks can ensure both operational stability and stakeholder transparency across multiple generational transitions.

Tata Group (India)

The Tata family has built one of India’s largest and most respected business conglomerates while consistently maintaining strong ethical standards and substantial philanthropic commitments across multiple generations. Their approach combines professional management with family oversight, creating a model that balances commercial success with social responsibility and has enabled sustainable growth across diverse industries from steel to technology.

Bosch (Germany)

The Robert Bosch Foundation structure demonstrates how family values and founding principles can be preserved while enabling professional management and aggressive global expansion. This unique ownership model allows the company to maintain its long-term strategic focus and commitment to innovation while accessing the capital and expertise necessary for competing in international markets.

The Future of Family Enterprises

These companies continue evolving to meet modern challenges while preserving their core advantages. Key trends shaping the future include:

Technology Integration: Digital transformation remains critical for competitiveness, with successful companies investing heavily in technology infrastructure and capabilities.

Sustainability Focus: ESG considerations increasingly influence strategy, with family-owned companies often leading sustainability initiatives due to their long-term orientation.

Global Expansion: Many companies are expanding internationally while maintaining their cultural identity and family values.

Professional Governance: The most successful family firms continue professionalizing their governance structures while preserving family involvement and vision.

FAQ

What is the biggest family company?

Controlled by the Walton dynasty, Walmart is often considered the largest family-controlled by revenue, generating approximately $648 billion in 2024.

Why should you consider starting a family business?

Family-run firms provide unique advantages including long-term thinking, patient capital, strong values alignment, and built-in trust among stakeholders.

Is a family business a firm?

Yes, the terms “family business” and “family firm” are used interchangeably to describe enterprises where family members hold ownership, management, or governance roles.

What are the different types of family firms?

The main types include founder-led enterprises, sibling partnerships, multi-generational dynasties, and family-controlled public companies.

What are the biggest challenges in family business succession?

Key succession challenges include managing family dynamics, ensuring competent leadership transitions, maintaining business continuity, and balancing family interests with professional requirements.

Conclusion

Generational enterprises are strong catalysts for economic expansion because they combine the flexibility of entrepreneurial leadership with the stability of long-term planning. These organizations routinely outperform their peers when they integrate professional governance, digital maturity, and transparent oversight with their innate advantages of loyalty, sustained values, and patient capital.

The secret to success is striking a balance between tradition and organization, fusing strategic vision with emotional legacy, and upholding unambiguous accountability for all parties involved. Companies that accomplish this balance, such as industrial titans like Bosch and retail behemoths like Walmart, show that dynasty-led enterprises are not only surviving but also driving the modern economy

Recognizing these dynamics offers important insights into one of the most resilient and prosperous business models in the global economy, regardless of whether you’re thinking about launching your own company, joining an already-existing family business, or investing in family-controlled businesses.

Comments are closed